Encoded in our bodies is the master blueprint, the DNA Helix. The structure of the DNA Helix represents energy efficiency. The structure looks like a coil, a spring.

Springs are efficient ways to transfer energy. That could look like the coil springs on your automobile absorbing the bumps in the road. These are called compression springs. They absorb energy and compress. The energy is then released and the spring returns to its “normal” length. Tension springs work from the opposite perspective. Your garage door has huge closed coil springs. When you open the door, the spring goes from its resting length to its expanded length. The energy to “stretch” the spring is released to assist in closing the garage door.

There are many kinds of springs. We use springs in all the machines that we encounter in our lives. Fascia is the spring in our bodies.

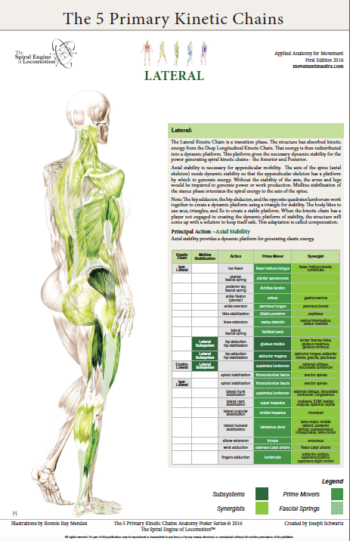

Fascia has several roles in our bodies. It is also called connective tissue which is the primary component of our structure. Fascia wraps and binds every part of our body creating a unified whole. Fascia is also a communication avenue for the nervous system. Messages about our environment and movement are relayed through fascia. Fascia plays a crucial role in our movement.

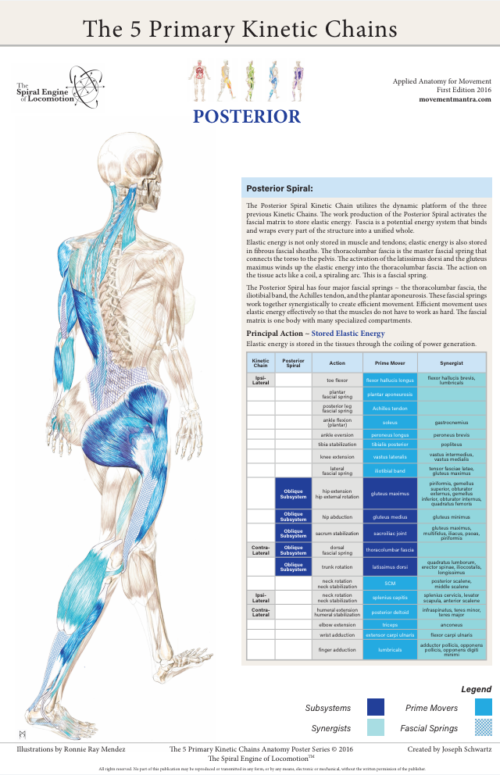

At a muscular level, fascia binds all the different layers into a unified muscle belly. Muscles act on the fascia, the fascia translates that energy into movement. The energy potential of fascia is relative to the ability of the tissues to move between the resting length and its coiled activated length. The coiling action is storing elastic energy and likewise, the uncoiling is the translation of elastic energy. The ability of tissues to store elastic energy is directly proportionate to the work capacity of those tissues.

The iconic model airplane with a rubber band that drives the propeller is a great example of stored elastic energy. We wind up the propeller by hand. That energy is then stored into the rubber band. When we release the propeller, the stored elastic energy is then translated into the propeller. The propeller spins the opposite direction giving the craft movement, flight.

Our bodies are not so different than the model airplane example. The fascial sheath of the thoracolumbar fascia is the primary fascial spring for locomotion. When we walk, the torso is twisting on the axis of the pelvis. This rotary action of the posterior spiral is winding up elastic energy into the thoracolumbar fascia. The stored elastic energy is then released into the complementary movement resulting in forward motion.

This is a simplified example, as the thoracolumbar fascia has the potential to store and release elastic energy in all three planes of movement. When you add two or more planes of movement together, the result is a spiral. During the gait cycle, all 5 Primary Kinetic Chains are working together synergistically, and the body’s movement can be described as complementary, contralateral spirals. This is the essence of The Spiral Engine of Locomotion™.