The Five Primary Kinetic Chains rely on a fundamental principle: efficient movement requires the integration of a stable yet dynamic foundation so that the body can generate the power needed for locomotion.

The Anterior Spiral is a culmination of everything that we’ve discussed previously. As such, let’s review how the previous four kinetic chains have worked together to get us to this final kinetic chain.

The Intrinsic system is related to the nervous system and breath. The breath is a barometer for our movement. How our breath is integrated with our movement determines how our nervous system responds. If we move in a manner by which the movement breathes the body, the sympathetic nervous system can remain down-regulated, thus giving us access to refined motor control. If instead our breath reaches the threshold of cardiovascular distress, or we are holding our breath out of bracing or fear, our sympathetic nervous system becomes up-regulated and arms the body with a flood of chemistry.

One of the markers for stress tolerance is the capacity to return from an aroused sympathetic nervous system back to a calm parasympathetic down-regulated state of being. A large percentage of our population is stuck in an up-regulated sympathetic nervous system. This is a stress reaction that results in inflammation in the body contributing to decreased healing and regenerative ability. As a result, it is becoming popular to “train” the vagus nerve — the tenth cranial nerve — to experience arming and disarming the nervous system.

There are some very good modalities to specifically address an up-regulated sympathetic nervous system. Our personal practice is one way we can take responsibility for our stress levels. Tia Chi, Qi Gung, Shamatha Meditation, and Yoga are but a few examples. I personally find getting acupuncture to be very much a sattvic practice. I go very deep into meditation as I’m observing the energy shifts in my subtle body. For people that are attracted to manual therapy, Cranial Sacral Therapy is a wonderful way to engage the nervous system and the breathing apparatus. Nervous system health very well may start with the subtle aspects of how the cranial sutures are integrating with breath and movement.

The Deep Longitudinal Kinetic Chain is about how we interact with gravity and shock absorption. Our bodies are under a constant compressive force. The energy of the compressive force changes as movement and locomotion further generates kinetic energy. The energy of our bodies in motion must be absorbed and translated. The energy is distributed across the fascial fabric of our bodies.

This energy becomes a dynamic platform, the Lateral Kinetic Chain. The Lateral KC provides dynamic stability so that the appendicular skeleton has a foundation from which to work off. Without this foundation, the body would be at a disadvantage in generating stored elastic energy.

In developmental movement, the reflexive motor learning that is hard wired into our nervous system, we see that the movements are all about creating dynamic stability with the intention of getting us upright and using a bi-ped strategy of locomotion, the walking gait.

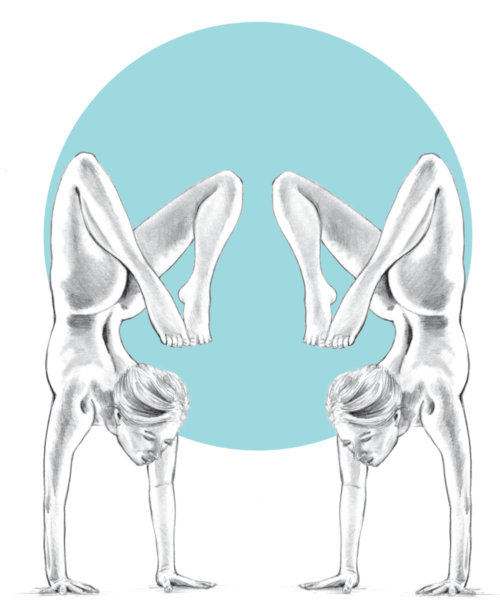

With an established dynamic platform, we have the capacity to store and release elastic energy. Elastic energy is stored in the tissues in two modes: lengthening or stretching and coiling or compressing. When tissues lengthen or stretch, the fascia’s elasticity stores energy. This would be like stretching a rubber band across your finger and releasing it; the rubber bands soars across the room. Likewise, winding up the rubber band on a model airplane illustrates the second mechanism of storing and releasing elastic energy. As the rubber band coils tightly, energy is stored; more coiling equates to more compression that stores energy to release.

The Posterior Spiral Kinetic Chain is the avenue the body uses to coil elastic energy into the fascial springs that perpetuate the energy of the walking gait. The body is utilizing both modalities (lengthening and coiling) for activating the fascial fabric to generate stored elastic energy. As the Posterior Spiral KC is coiled to release that energy, the ipsilateral anterior spiral is lengthening. It is a coiling of one side of the body and a lengthening on the opposite. The body is utilizing both pathways simultaneously, to generate stored elastic energy.

The Anterior Spiral completes the gait cycle. Elastic energy up to this point has been stored into the tissues, and now the body is poised to do something with that energy. The body will now translate the stored elastic energy into the complementary movement. The forward motion generated by the push of the posterior spiral is realized through the leg swing of the anterior spiral.

The ability to effectively store and release elastic energy is paramount to athletic performance. In the video, notice the quality of movement this athlete displays. The timing of arm drive and leg drive, the depth of absorbing kinetic energy, and how the explosive energy increases with each shock absorption phase. Her movement is brilliant and demonstrates healthy integrated kinetic chains at work.

The 5 Primary Kinetic Chains working together create an integrated whole. If one or more of the components are unable to engage, then we need to isolate the issue and through motor learning, reengage and integrate back into the whole. The kinetic chain charts are meant to be a map for inquiry, as we explore who is playing and who is not, the charts can help us to discern what disengaged players need to get back in the game.