Having a code of ethics is imperative for a healthy practitioner-participant relationship. This also extends to the learning environment with our peers. As therapists, we have a responsibility to create safety for both our clients and ourselves. In the following content, we combine how we keep the container safe for our clients, ourselves, and the learning environment in a seminar.

Tenet #1: Keeping the Container Safe

The context of the word container is appropriated from psychology. The container refers to the available coping strategies we have learned as a protection mechanism. Keeping the container safe builds safety in the nervous system through displacement rather than replacement. What does this mean?

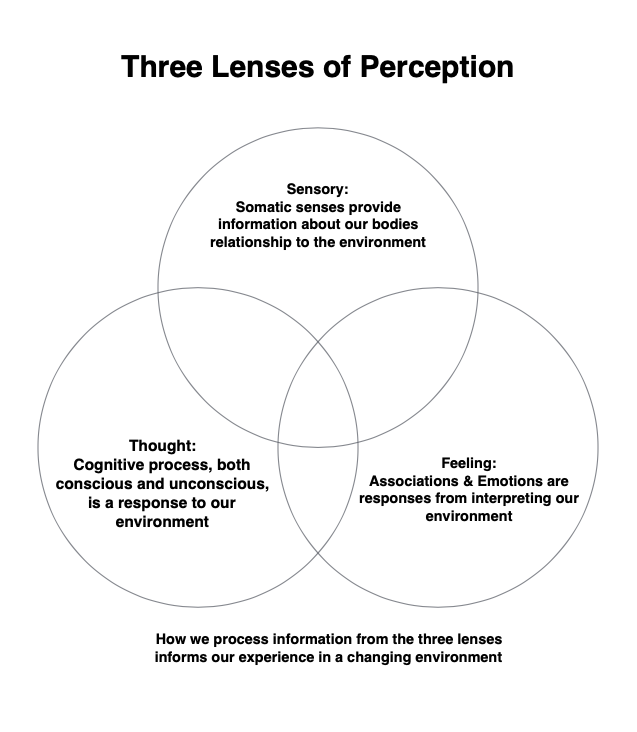

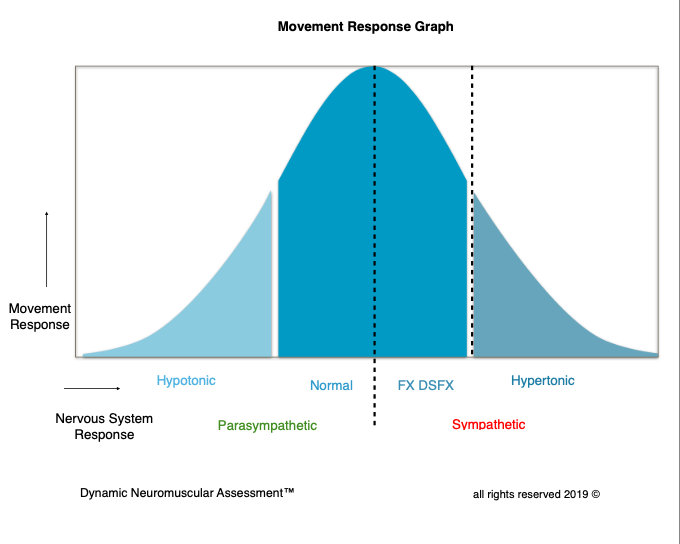

Within a therapeutic setting, we are ultimately assessing how our clients’ nervous systems (containers) are adapting to their environment. Our nervous systems have three ways in which to adapt to our environmental stress: beneficially, neutrally, and maladaptively. In the therapeutic context, we are not so much concerned with beneficial or neutral strategies. Instead we are looking for maladaptive strategies so that we can employ the corrective therapeutic intervention. While at one point that strategy had been necessary and appropriate, maladaptive strategies are not sustainable and lead to secondary maladaptive compensation.

Here’s the problem:

We cannot simply remove a maladaptive coping strategy. This creates a void in the container. That void is then replaced with something. More often than not, that “something” is maladaptive as well and potentially has an adverse outcome.

Here’s the solution:

We must honor the survival-based strategies of the nervous system. We must with clear intention displace a maladaptive strategy with a beneficial coping strategy.

There are several steps in learning the how and why behind the template we use in Dynamic Neuromuscular Assessment™ . Understanding the nature of compensation and how to have a conversation with the nervous system sets the foundation for all of our assessment strategies.

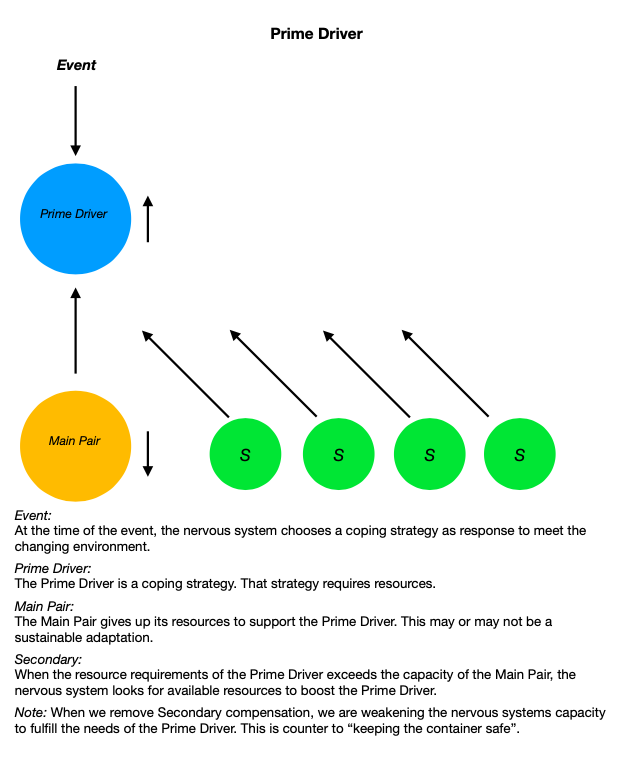

Let’s explore the nature of maladaptive compensation further. The needs of the changing environment, an event, prompts a response from our nervous system. The initial response becomes the prime driver. When the nervous system perceives that the prime driver doesn’t have sufficient energy to sustain the adaptation, it will then recruit more compensatory players. These are referred to as secondary compensations. Their role is to boost the energy level of the prime driver.

If we remove a secondary compensation, we are potentially weakening the prime driver. This is effectively creating a void in the container. The analogy of the three-legged stool works well. If we kick out a leg of the stool, a secondary compensation, the stool often becomes unstable and crashes.

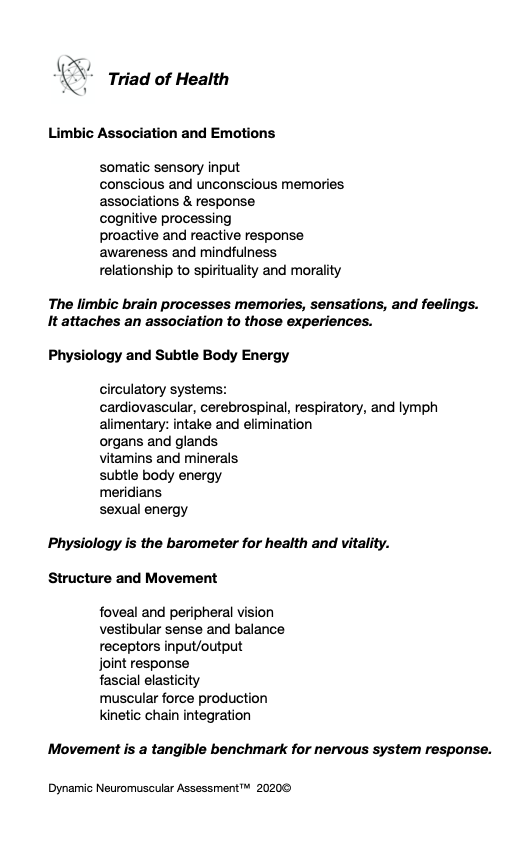

The nervous system has many options for filling the void created by removing secondary compensation. The trine of Applied Kinesiology: movement and structure, physiology and subtle body energy, and limbic associations and emotions become the subsets of options that the nervous system can utilize to boost the energy of the weakened prime driver. This is potentially disastrous when the nervous system chooses an energy system from our physiology or limbic associations. When we see our clients having adverse responses to treatments, this is often what is happening.

The template we use in Dynamic Neuromuscular Assessment™ addresses this in multiple ways. Module One is entirely devoted to acquiring the nuances of how to safely have a conversation with the nervous system. When we can effectively have a conversation with the nervous system, then we can recognize the markers needed to maintain a safe container, both for our client and for ourselves as practitioners.

Creating a safe container begins with the practitioner.

Container

Keeping the container safe starts with understanding the term container. The container refers to the coping strategies that we employ that keep us safe. They include setting clear boundaries and grounding. When our container doesn’t have appropriate coping strategies, inappropriate elements can enter our personal energetic field and cause disruption or harm. Keeping the container safe is necessary for our physical, emotional, and spiritual well-being.

Keeping the container safe starts with our intention to create a beneficial environment. We have an opportunity to grow and learn when we are safe. This requires mindfulness.

Mindfulness is awareness and in this instance means being appropriately responsive. Be the observer before you speak or act. Being a facilitator of a healing process, one would consider first “to do no harm.”

Boundaries

Boundaries are integral to the container. Boundaries are the intention we set that brings into our energetic field what is appropriate and safe. The spectrum of individuals we encounter will challenge our boundaries. There is a certain amount of vigilance needed to reinforce and maintain the sustainability of our boundaries. Maintaining awareness and mindfulness will keep the container safe for both ourselves and our clients.

Developing boundaries starts in the classroom with a teacher/student relationship. As a student grows into a practitioner, then the same clear boundaries extend to a practitioner/participant relationship.

Grounding

Grounding starts with intention. Our intention is to maintain a clear and safe energetic field. This is deeply personal and affects all those we meet. Grounding exercises can bring awareness to outside elements “sticking” to our energetic field. Here is a short list of grounding exercises you can do to clear and maintain your energetic field.

Getting barefoot on the earth

Imagining being connected to the core of the earth

Sitting at the ocean feeling the rhythm of the waves

Laying on the ground staring at the sky

Salt baths

This brief introduction is meant as a summary. I invite you to expand your understanding by researching how you can better create a container, set boundaries, and bring grounded mindfulness into your practice.

TLC, a template for a safe container.

T ~ Touch

L ~ Language

C ~ Choice

Touch ~ Safe touch is vital to create a safe container

Safe Porting

Safe Porting is a communication model that brings mindfulness to touch. The essence of Safe Porting is to inform another person what you are going to do before you do it. This clarifies intention before action.

We use Safe Porting to let the client know what is happening next or ask their permission to continue. This has two beneficial aspects. First, it prepares the person for contact. The nervous system is less likely to go into a defensive mode when it is understood what is happening next. This removes the surprise element. The second aspect is that Safe Porting empowers personal choice. Yes, I would like you to proceed. No, I would prefer you not proceed.

Language ~ The words we use affect people’s response

Be clear in the language you use and the intention behind those words.

Mutual respect starts with thought, thoughts become words, and words become action.

There is zero room for locker room talk, sexual innuendo, or sexual harassment of any kind.

Inappropriate or leading questions are disrespectful of another person’s process and privacy.

Ask yourself before you speak: Is it kind? Is it truthful? Is it necessary? Do some self examination. Do you use nocebo language in your communication?

Choice ~ Empowering another person with choice keeps the container safe

Ask the question: would you like for us to continue with XYZ?

Double check with an indicator. Ask if it is safe to continue. While an individual may give us permission to proceed, that is that person’s mind answering the question. The mind can construct and mislead, while the nervous system knows the truth of our capacity to unpack and process the information received in a therapeutic process. We do not want to open the preverbal Pandora’s box if that individual does not have the inner resources to process and close their container appropriately.

Safety for the Classroom

Developing the mutually respectful teacher student relationship, this includes assistants also, creates a safe container in the classroom. Different students will have different needs and responses. Honor everyone for their uniqueness. Respecting the space for all participants means being sensitive to other people’s needs and responses. During different breakouts with the material, you and the participant on the table may be okay with the process, other participants may not be. Monitor your intention, language, and action. Other people that have had similar experiences may be sensitive to the subject matter. Be considerate of other people around you.

Safety for the Client

Clients will present a spectrum of response to different modalities. Continually check in with your client to ensure their safety. They may not have the capacity to know their boundaries are being crossed. Use a qualified indicator to monitor the safety of their nervous system.

When your client has an emotional response, remain present and grounded. You are the anchor to assist them with their process.

Safety for the Practitioner

As a practitioner, maintain clear boundaries, this keeps you safe. Continually check in with yourself and trust your intuition.

If you realize that the component you are treating is something that you are personally experiencing or triggered by, be aware that your own relationship to the presentation can be unsafe for both you and the participant. If you are triggered by the presentation, your assessment and treatment may be inappropriate, and you can easily find yourself in transference situation. This is when the participant becomes a surrogate for the practitioner’s nervous system. If/when this occurs, the appropriate thing to do is take a little space to regroup, ground, get a sip of water, and reevaluate. Being a facilitator of a therapeutic process is recognizing when it is appropriate to stop and take inventory.

DNA™ Specific: Using a Menu

DNA™ uses limbic resonance to ask the nervous system questions. This can pose a unique challenge for not crossing ethical boundaries. It is primary to consider that we keep the container safe by asking only appropriate questions while respecting the privacy of others.

During assessment, we will be using a menu and asking questions. Ask permission to proceed with questions or the process.

Holding space needs to be appropriate to the issue. This means no leading, pushing, or digging into the emotional content of an event.

When asking questions, ask to yourself rather than out loud. Verbalizing can make the client uncomfortable, embarrassed, or potentially trigger a limbic reaction.

When working with an emotional correlation, have the participant hold a thought in their mind rather than ask is the issue XY or Z. This ensures privacy and keeps the participant empowered while creating a safe space.

If you’re not comfortable with a correlation or unable to stay grounded do not attempt to treat. This is an important transference safety issue.

If you’re not comfortable with the location or the point of contact of a TL, ask the client to do it for you. If they are unsure, show them on your body and use clear language. You can also ask them if it’s okay for you to assist. Then guide their TL to the specific location.

Be cautious and aware of the language you use. The power of the words you choose affects the outcome.

If you get to an emotional piece, remember to pause and take a breath. Continue with deep breathing while client-releasing. Consider yourself as simply a vessel for the energy to flow through. Breathing helps you keep the energy moving.

How we work with the limbic system affects the outcome of the process. In our DNA seminars we demonstrate the proprietary process of Self Rescue. This is a potent tool to tone down the energetic charge of a compartmentalized event/association.