From my perspective, there is currently a fundamental problem in the manual therapy community. Manual therapy is predominantly a tool-based intervention strategy; consisting of many variations of tools and techniques. As a result, practitioners take the particular tool they’ve been educated in and apply it to the presentation of the client.

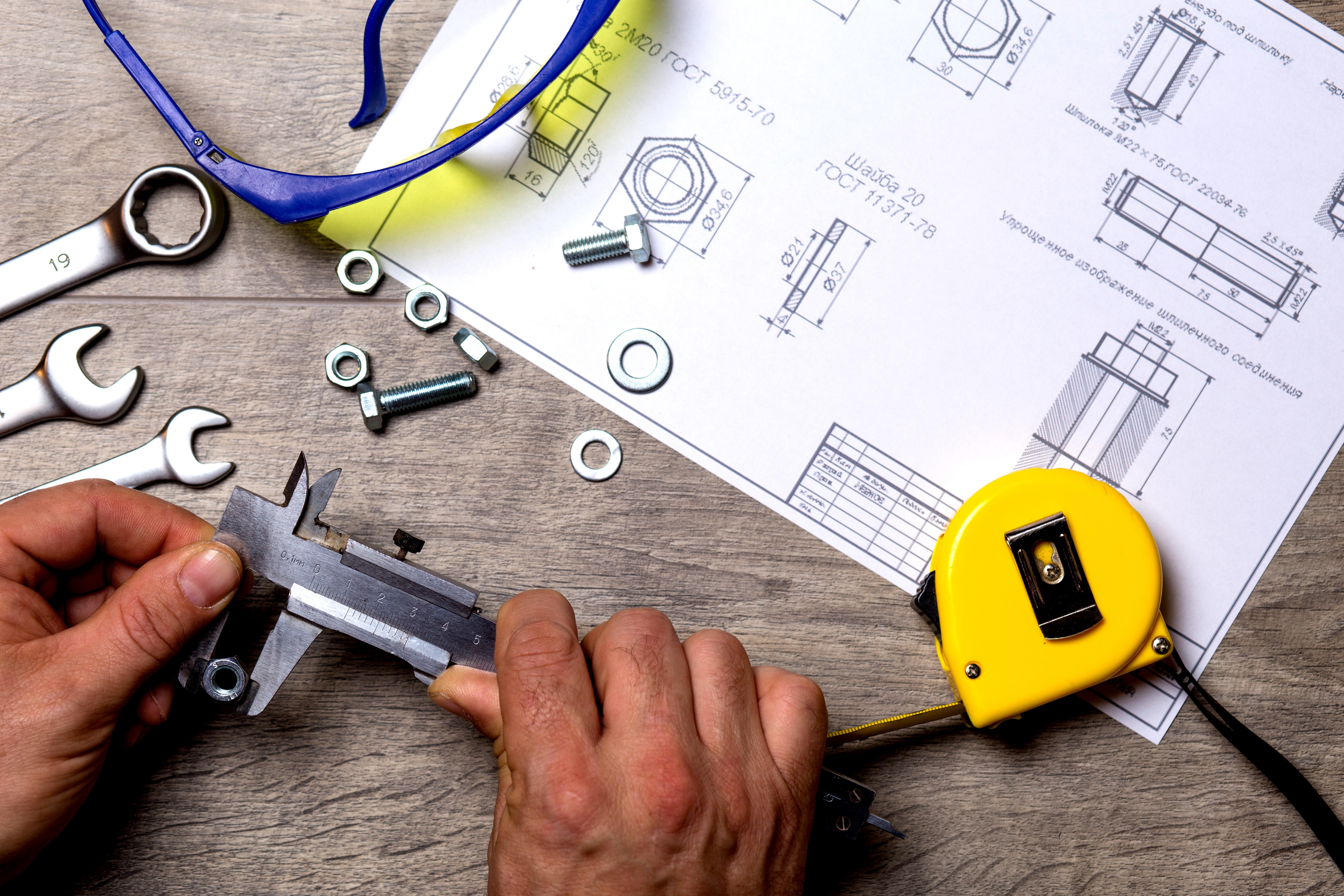

Being a former race car mechanic, I liken this analogy: If I purchase a brand new shiny 10mm wrench, am I going to go around the car and look for fasteners it might fit? That doesn’t make a lot of sense, does it? Let’s dive a bit deeper.

We see a plethora of technique-based courses being offered in our profession. There are many reasons why we need to have an array of tools available to us. However, the tools themselves often distract us from finding the causation of each unique presentation. When we are simply applying a tool to a problem to see if the problem changes, we are guessing. This has the potential to be negligent.

I recognize that the statement that a tool-based intervention is potentially negligent is a bold statement. Let’s build some context that supports the statement. We need to consider two specific variables in an individual’s presentation.

Adaptation

Adaptation is a learned coping strategy. Understanding why that coping strategy was implemented by your client’s nervous system is the primary consideration. That person’s experience has biopsychosocial factors that influence how their nervous system chose to cope with and adapt to the changing environment around them.

Compensation

The combination of symptoms based on a nervous system’s chosen adaptive strategy, is not consciously chosen. It is instead a function of the survival-based nervous system. Adaptation is mostly unconsciousness behavior. However, there are exceptions when we consciously add elements to our environment for beneficial change — like changing one’s diet or engaging in a fitness plan. Maladaptive compensations are often driven by our unconscious, even if it seems like we are making conscious choices.

Here’s a hypothetical presentation that illustrates how a tool-based intervention can be negligent. Let’s use an example of regional interdependence, where one region of the body compensates for another region of the body not participating. For example, a client comes in with sacroiliac pain. The function of pelvic sacral stability is diminished in some way. Using the model from Lovett Reactors, the therapist traces the instability to the jaw. The therapist then treats the jaw.

There is a fundamental problem with this. While the pelvic sacral stability issue is a symptom of the jaw, more times than not, the jaw is a symptom of something else. That something else is related to an experience, which became an association that has an array of emotional responses. The symptoms we are seeing in the jaw is related to a past experience and a limbic association. Effectively, what the therapist has inadvertently done is remove the coping strategy of the limbic system. The potential for this to blow up is pretty high.

Now let’s look at a real life example. This occurred in a seminar that I attended several years ago. A combat veteran was getting a neurological treatment from a colleague to correct a movement dysfunction. Unbeknown to the therapist, that movement dysfunction was related to a combat experience. The person on the table had a full blown PTSD incident while being treated. Afterward, he became suicidal and had to be on suicide watch while his limbic system reorganized to find a new coping strategy to compartmentalize the traumatic event.. This kind of response can happen on a spectrum from mild to full blown PTSD flashback like this example. When we are treating symptoms, we are potentially creating a vulnerability in the coping strategy of the nervous system.

There is a solution to this problem of tool-based therapeutic intervention. The solution is an assessment-based process that determines the root cause of the individual’s presentation. That assessment process must consider each aspect of the presentation as a potential symptom. The symptom-causation relationship must be traced to the driver of those symptoms. That driver is the root causation. That assessment process must take into consideration the entirety of the biopsychosocial model. The down side of this is when the causation of the individuals presentation gets out of our scope of practice. This is when our referral network becomes very important.

As therapists, we can do better. We can advance from being the hammer and seeing every problem as a nail. Instead, we can hone our assessment strategies to derive the appropriate tool that is needed — see The Five Tenets of DNA™ to learn more. We can determine if it is safe to use that tool. We can live up to the first rule of the Hippocratic oath: Do No Harm.