Today I’m sharing a recent conversation between a colleague and I regarding limbic versus cognitive behavior that I hope brings you some food for thought:

Some people find the holidays a stressful time of the year. Stress correlates to an up-regulated sympathetic nervous system. We often hear “take a deep breath” as an easy way to regulate.

Let’s reframe this slightly. To take a deep breath requires being in action. With an up-regulated sympathetic nervous system, we are already doing too much. Instead, let’s be the observer.

Imagine that that the breath is like a glass of water. When you fill a glass with water, the water fills from the bottom to the top. Conversely, when you empty the glass, the water empties from the top to the bottom. As you observe your breath, feel the inhalation expanding the belly, the lower ribs, then the upper ribs and clavicle. And as the exhalation happens, watch the breath descend in the reverse order.

Being the observer allows you to tune into the sensation rather than focus on accomplishing something. This subtle reframe has a profound effect on your experience in that moment. We can’t think our way out of a sympathetic nervous system response, however we can feel our way through as we navigate sensations.

Amy Maynard Buckles: “Being the observer allows you to tune into the sensation rather than focus on accomplishing something.” Love that! Why can’t we think our way out of a sympathetic nervous system response?

There is a long version and a short version to that question.

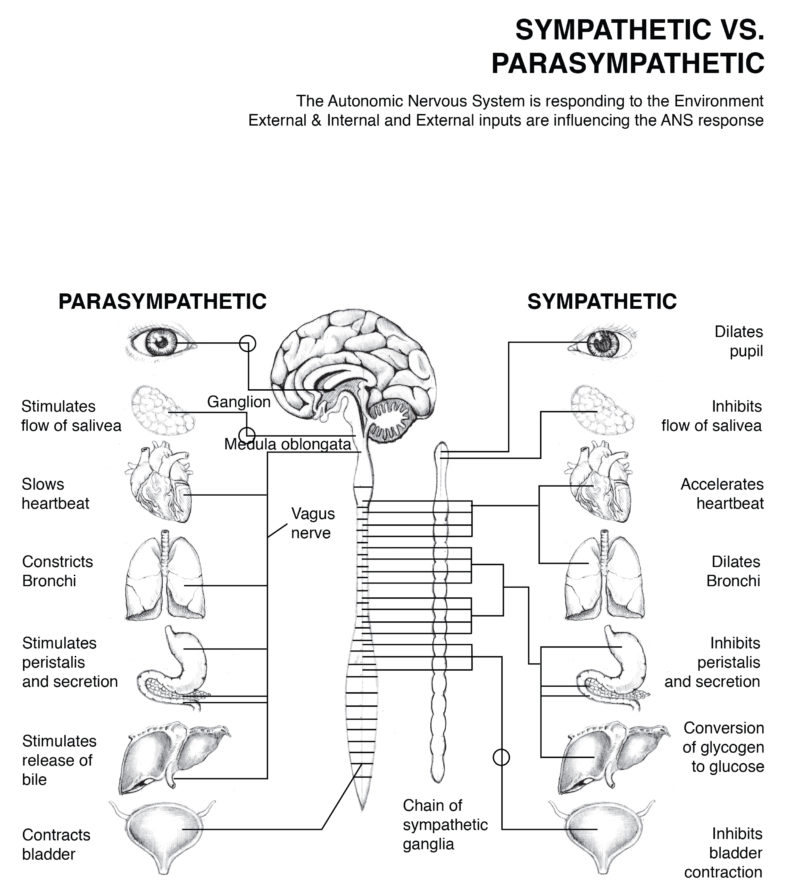

The short version is related to the mechanism of information gathered by the Autonomic Nervous System (ANS). The limbic inputs, the sensory apparatus of the body, the five-traditional and the non-traditional senses communicate with the ANS. That information is collated and prioritized based on past experiences: our associations and hard-wired reflexives. The most relevant way that we can affect our ANS is through the sensory input of the limbic channels. This points to why breath work, aromatherapy, and the five tastes are such powerful tools that we can utilize to make change in the response to our environment.

Personally, I am most interested in the non-traditional senses. The information we take in from our environment, such as electromagnetic fields, barometric pressure, bioelectric energy, and so forth. There are unknown realms of information that we are experiencing and collating at an unconscious level. This spectrum of perception I find fascinating.

The tip of the iceberg analogy also works well here. Twenty-five percent of information is perceived consciously, while 75% of information largely goes unperceived by our consciousness. That is huge.

Buckles: Great explanation and info to share! I am curious as to your thoughts on how much of our conscious thoughts, with practice, could change the ANS response. Like in a panic attack for example. I understand that while focusing on breath, we are out of our heads and more into our body awareness. Which, would activate the PNS. To me, that’s not thinking. However, if we gain information about our environment, our safety, and other sources of input and responses…then we can consciously choose to think differently. Hopefully not only to prevent ANS distress, but also reverse or stop it.

“consciously choose to think differently”

That is a key to cognitive thought process.

Here is the big challenge to overcome: thought is chemistry. The Law of Adaptation says that the body adapts to its environment regardless of outcome.

Emotions are a specific cocktail of chemistry. We get better, more efficient at making the “cocktails” of our predisposition. Those chemicals require receptor sites to plug into. Over time we end up making more of that unique composition of chemistry to fill the receptor sites. Through adaptation, we become addicted to thought. Overcoming that requires conscious effort.

If our predisposition is to respond to a situation in a familiar way, reproducing those feelings becomes easier each time we have them. You can see this in people that have “knee jerk reactions” — these folks are quick to produce the chemical signature they are familiar with.

Some people have the disposition to do that kind of work on a cognitive level; change your thoughts and change your behavior. Others need stimulus from the other part of the brain, the limbic center. These are the people that do better at maintaining attention on sensation.

There is a loop in the brain and how we process our environment:

Limbic—>Association—>Cognitive

Sensory—>past or projection of future—>Ego or survival

Our ability to interpret the information of our sensory apparatus, and reframe from a place of being hijacked by associations that are interpreted by the ego, define our ability to cope.